Back to overview

The personal development of academics

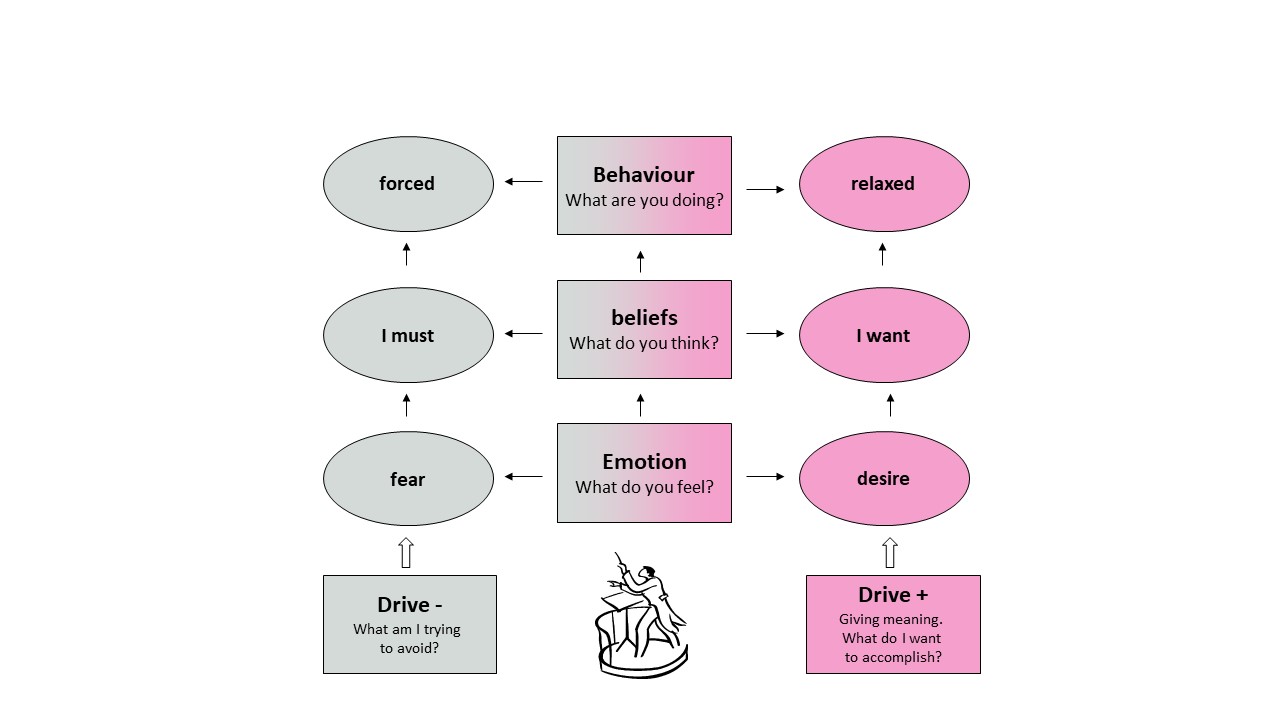

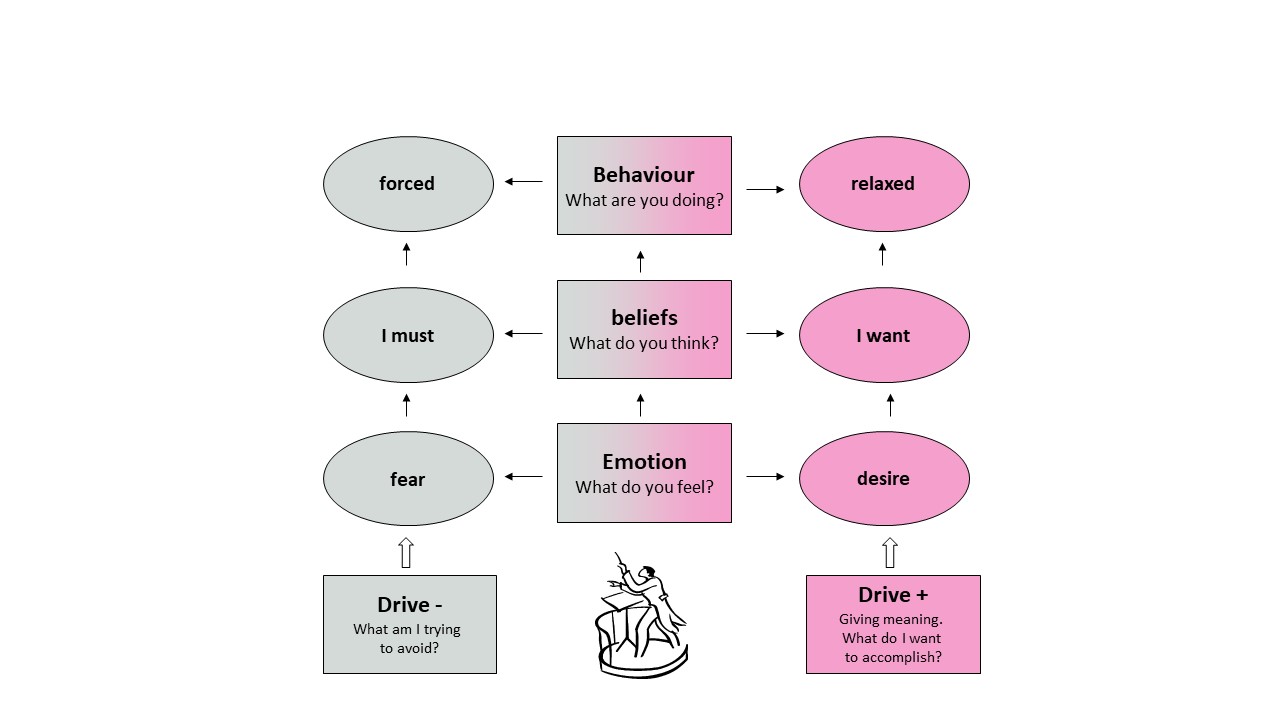

Academics love what they do. Curiosity, wanting to know how things work are part and parcel of their job description. Add to that a drive to make things work even better and you have the quintessential academic: someone who doesn’t see research as work but as part of everyday life. Academics also want to make their mark on the world and excel in their area of expertise. Competition with colleagues working in the same field can be fierce. Funding is scarce and there are many candidates. This is a source of tension. On the one hand academics are motivated by the need to explore and discover. On the other they are spurred on by their ego or the fear of being outshone by colleagues.

These positive and negative drives are waging a constant battle.

Fear of failure lead to thoughts of all the things you ‘must’ do.

For example, I must..

..get funding

..be the best in my field

..publish this article

..get that guest speaker job

These thoughts can be very stressful and may lead to forced and adaptive behaviour aimed at avoiding failure (left column).

And although it can be very sensible to be aware of possible risks or dangers, you will find that it takes a lot of energy to move forward if avoidance of failure is your main drive.

A positive drive will make your involvement in science a pleasurable experience. Your thoughts are fuelled by enthusiasm and the will to achieve something. Doubts and worries are put aside so all your energy can be focused on the research in hand (right column). Far from depleting your energy, this approach generates the kind of energy that moves mountains.

In short, there are two kinds of drive. One is fuelled by ‘fear’ and aimed at avoiding failure. The other is fuelled by enthusiasm and confidence and is aimed at realising ideals. Both drives produce high-level scientific output which can make a difference in this world and one is not necessarily better than the other.

Finding a balanceThe trick is to achieve a healthy balance between both drives. The conductor in the image is continually weighing up interests and making choices, preferably by using his common sense. Emotions may be perceived as ‘true’ but they are not always based on reality in the ‘here and now’.

A good example is a presentation where the speaker experiences feelings of shame because he was laughed at when giving a class talk in school. The chances that history will repeat itself are very slim and yet the similarities in the circumstances elicit an emotional response.

The current pressure to perform is not making it easy for academics to achieve a balance between the two drives. The academic world is focused on excellence on all fronts. I have been working with academics for the last 15 years, including some very successful ones. I have yet to meet one who ticks all the boxes. I think it is safe to assume that the perfect academic doesn’t exist. A relentless emphasis on excellence will not create better academics. It will only increase the pressure on people who are already highly motivated to achieve results. In my opinion it would be far more productive to acknowledge that every academic has his own personality, style and skill set. It would be better to encourage them to organise their research team in such a way as to make full use of the talents and skills of the people in it.

Academics have a way of turning on the pressure on each other as well. 60 hours a week is the minimum if that grant is going to be bagged, they tell each other. The result is that a weekend spent watching the children play sports feels like a dereliction of duty. At the same time they feel guilty for not spending enough time with the family.

This is just one of many examples that show how ‘must’ and ‘want’ are in constant competition. Decisions, sometimes more than one, have to be made every day. Should I take a seat on this commission? Do I want to be involved in this consortium? Can I afford to take time out for a holiday or not? These are the type of decisions academics grapple with. It takes courage to make choices which improve personal wellbeing because the underlying fear is always that these can adversely affect a career.

This often leads to academicss – and non-academics – to bite off far more than they can chew, causing anxiety, sleeping problems and an overwhelming tiredness. Eventually the stress of it all will result in a breakdown.

The only way to find a balance is to learn how to deal with feelings of fear, to choose differently and to reconnect with positive drives. That demands a robust sense of inner leadership, particularly in the environment in which academics have to function.

Most people need help to achieve this and it often means they will be confronted by their own limitations first. Coaching is a good way to help them on their way.

Aletta Wubben

Owner, coach & trainer van Aletta Wubben, Mens- en organisatieontwikkeling